If you’ve marveled at space news recently, there’s a good chance it’s thanks to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. This arm of Nasa is responsible for the most ambitious of missions, like sending robots to Mars and, most recently, the Juno spacecraft to Jupiter.

But the JPL has another under-the-radar mission: uniting two uncommon bedfellows – design and science – in new and meaningful ways.

You’ve probably never heard of the Studio at JPL, a group of rocket-science misfits who roam the facilities, offering their not-so-traditional design skills to engineers. You’ve definitely never seen their digs, a trailer on the outskirts of campus that looks like a science fair exploded on the inside. But you may have already seen their work.

The studio comprises eight jacks-of-all-trades who have experience in sci-fi movie effects, anthropology, advertising, architecture and illustration, among others. They work like freelance contractors, usually juggling at least five projects apiece.

For example, Joby Harris has created models of Saturn’s moon, Enceladus, and sketched out space helmet designs. And Liz Barrios recently helped an international team of scientists visualize what the surface of a comet would look like for the Rosetta spacecraft landing. (Turns out, the texture of pancakes is a very close comparison.)

The team is also tasked with quietly sprinkling scientifically accurate awe all over the JPL. In the nondescript building number 180, for instance, there’s a sculpture – a column composed of plastic rods that stands about 15 feet high – set to dramatic effect alongside the words, “Dare Mighty Things.” Every few minutes, bars of light, varying in size, drip from above and shoot up from below the column. It’s reminiscent of a particularly active glowworm cave. In reality, it’s the beating heart of JPL’s work.

The sculpture pulls data from a nearby building in the dark room of Mission Control. There, neat desks are arranged audience-style, facing ever-updating screens displaying the real-time activities of the 13 antennae in the Deep Space Network (DSN).

The sculpture is displaying data from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), which exchanges information with the Wall-E-esque Curiosity rover. When an engineer in Mission Control types directions on a keyboard, Curiosity will do what it’s told. It will then send the data it collects back to the MRO high above the surface of Mars, which sends it to the antenna DSS 55 in Madrid, Spain, which sends it back to Mission Control in Pasadena, which sends a stream of light shooting down the length of the sculpture in building 180.

All of this in real time, with only the delay of about 15 minutes that it takes for the data to travel 33.9 million miles from Mars to Earth.

The JPL is full of unassuming wonders like that – in this case, and in many others, thanks to the studio.

The JPL’s sprawling Pasadena, California, facilities resemble a very high-tech college campus, especially during summer intern season, when I went to visit. For space enthusiasts, it’s more like Disney World.

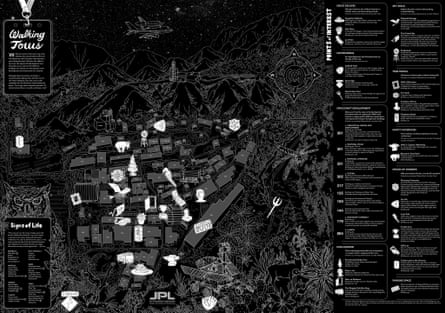

Every year, the lab welcomes about 50,000 visitors for free tours, complete with mini museums and 3D glasses. The visitor map looks like the brochure of a Hollywood studio backlot tour. Even the interesting facts shared with visitors align with a movie-script version of Nasa: maybe you’ve heard about the lucky jar of peanuts that must make an appearance in Mission Control at every launch. Or the “rocket boys” who founded the lab by blowing things up in an isolated arroyo.

In part because of its untraditional beginnings, and in part because it’s the only arm of Nasa that is managed by a private organization (the California Institute of Technology), the JPL’s culture has always been a little more freewheeling and entrepreneurial.

This could explain why, in 2003, Elachi decided to hire an art student and set him loose on campus.

Elachi had given a tour to Art Center president Richard Koshalek, who told Elachi that he needed an artist to share JPL’s complex work with laymen. “At the time, it was a fairly radical idea that we would need people from Art Center or similar places to help us communicate,” says Steve Matousek, who worked with Goods and team on a successful mission proposal in 2003.

But Koshalek already had a student in mind.

That student was Dan Goods, an artist with close-cropped hair and a notably even-keeled, humble manner. “I told him he had one year to demonstrate what he can do,” Elachi says. “Within a few months he was so popular and in-demand that we gave him the green light to expand his group.”

The studio’s work is arguably unique in all of Nasa, and inarguably represents a shift in thinking that’s happening in other small pockets – bringing art and science together on a more equal plane. Studio designers create art, yes, but they also contribute to the science happening at Nasa.

“Science and design aren’t typically used in the same sentence, but they should be,” says Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya. The neurologist-turned-designer recently created The Leading Strand to unite designers with scientists on similarly equal grounds. “Science is highly complex, and design as a field elucidates complex information. Designers try to understand by making systems, using color, conveying emotion. Scientists have their scientific process. In the end it’s all very creative.”

There’s no typical type of person who works at the studio, and there’s no typical day. Generally, members are working on project requests from engineers. Maybe they have a big-picture logistical problem they’re trying to think through, or they want to share their work with the public, or they just want a better-designed place to hang out. “It’s usually people coming to us, for all sorts of reasons,” Goods says.

The studio also creates art to communicate JPL’s work to the public, but it’s more immersive than the art Nasa has commissioned in the past, by the likes of Norman Rockwell or Annie Leibovitz. The Studio’s take is usually somewhere between an art installation, a public monument and an interactive museum exhibit.

When the Rosetta spacecraft landed on the 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko comet in 2014, the studio commissioned STUDIOKCA, an architecture and design firm, to create a 12-foot-long glowing sculpture, complete with a “tail” of water vapor that grew just as a real comet’s tail would. Another installation, the Orbit Pavilion, also designed by STUDIOKCA, will be on display at California’s Huntington library starting in October. There, visitors sit beneath a massive nautilus-shaped metal structure and listen to satellites passing overhead as if they were airplanes.

“We want to give people a sense of urgency about what we do,” Goods says.

The Studio does this for Nasa employees as well. There’s a digital counter next to the elevators in building 180, displaying three rows of numbers: how many planets have possibly been detected around other stars, how many have been confirmed as detected, and how many are in the habitable Goldilocks Zone that could support life.

“Now, we take a picture of this and send it to Nasa headquarters every month,” Goods says. “That’s how they update how many planets they’ve found.”

In another building, we approached a small meeting room labeled Left Field, “a brainstorming war room kind of place”, as Goods describes it. It’s where designers consult with engineers who must pitch potential missions to Nasa board members, down to cost estimates. That’s tricky because JPL’s missions usually involve, say, sending a spacecraft to Jupiter, arriving 10 years from now.

In 2003, Matousek asked Goods to help pitch his proposal for just that journey – the Juno mission – to Nasa review board members. The team brought a cohesive aesthetic to mission proposals, asked guiding questions, and created models to demonstrate that ambitious plans, like a huge solar panel, were in fact realistic.

“The studio takes something that seems hard to understand or difficult, but when you step away or get in the middle of what they designed, you go, Ah, of course! And the idea hits home,” Matousek says.

Their pitch emerged victorious. In July, Juno entered Jupiter’s orbit, sticking to the proposal Matousek and Goods worked on 11 years ago, including the cost.

“We’re not going to solve their differential equations,” Goods says. But Studio designers can tell when engineers aren’t on the same page, and they aren’t afraid to ask “stupid” questions to help the engineers “think through their thinking” – a motto of the studio. “They kind of have a permission, a freedom, to say things they wouldn’t normally say,” Goods says. “They start to talk about what they work on in different ways, especially when we ask a bunch of questions their peers don’t ask.” The designers are also rigorous about understanding the science: there are no artistic liberties when you’re demonstrating the feasibility of a $750m mission.

With this meeting of the minds, the JPL’s complicated work can better hit two notes – compelling storytelling and accurate, well-though-out science. That’s critical for the federally funded JPL, if only for the practical reason of maintaining budget. “We’re spending the public’s money and they deserve to know that we’re doing something really great with it, and that this is about furthering humanity,” says studio member David Delgado.

Still, ask any studio member why their job is important, and their answer will probably include another word: awe.

“One of my favorite moments was when I showed a bunch of scientists one of the pieces I’d done,” Delgado says. “He told me: ‘You’ve reminded me why I’m here.’”

If there were ever a time since the Space Race when Nasa needed to maintain, rather than create, high public interest – it’s now. Goods gives some credit to movies like The Martian that seem to say, “The future is here.” The technology looks more attainable; the concepts of space tourism and colonization mirror efforts that are really taking place from Nasa to SpaceX. The Studio team has seen the same enthusiasm for their own public campaigns, like a series of exoplanetary travel posters.

But they are readying for big changes in the next year. Elachi, whom Goods credits with “taking a leap of faith” on him 13 years ago, retired at the end of June. In 2017, Nasa is due for a new decadal survey, a report from the National Research Council that outlines what the agency’s priorities should be in the next 10 years. Not to mention, the new president of the United States can also dictate America’s space priorities for the next four years.

“When I first got here, we were going to go to Jupiter with nuclear power, create big telescopes in space to look for planets around other stars,” Goods says. “When George W Bush came in, he wanted to go to the moon and to Mars. Those other things got canceled. You can have an idea and then it’s no longer important for a decade. You just have to decide how you can best help.”

As Goods and I stood watching beams of light shoot from Voyager 1 in building 180, two VIP visitors entered the building – guests of Elachi. The visitors stood admiring the sculpture as their guide greeted Goods. “Dan is the guy who created this,” she told the guests, as a staccato stream of light erupted from the column – data from Mars.

Just another small wonder at the JPL.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion