The technology industry likes to talk about how automation is set to change the world. Chatbots present a new way of interacting with software, self-driving cars promise to reshape our cities, and the increasing capability of AI to handle ever more complex and “human” tasks could reshape our economy. But amid all the futurism, one thing gets lost: actual robots.

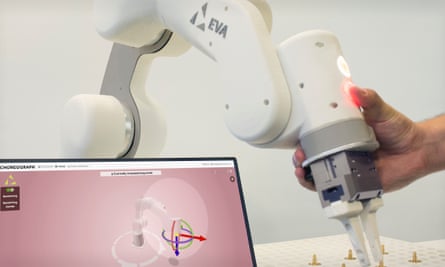

London startup Automata Technologies is one of those hoping to reverse the trend. The company makes a tabletop robotic arm, which it hopes will democratise access to automation for every industry by costing a fraction of the tens of thousands of dollars a typical industrial robot costs today – under £5,000 up front, or under £500 a month for a “robotics as a service” package. One thing that’s no different from the world of software bots is that this robot has a woman’s name: Eva.

I met the company’s co-founder, Suryansh Chandra, at Automata’s office in a “startup incubator” in north London. Hardware startups have very different homes to software ones. There are no shiny glass panels or fancy laptops cluttering up hot desks, instead Automata’s Eva prototypes sit amid a collection of cables, soldering irons and 3D printers.

Architects turned roboticists

Chandra, and his co-founder Mostafa ElSayed, don’t have a history in robotics. They’re both trained architects who worked for the studio of Zaha Hadid, the designer of the London Olympics Aquatics Centre. Their career pivot came, not out of a desire to make their fortune as a technology startup, but from need.

The pair had been assigned to work on the studio’s pavilion for the Venice Biennale, a towering steel mushroom made from 500 uniquely shaped aluminium panels. As a show of architectural prowess it was formidable: the panels were too thin to hold up the structure on their own, so were folded to increase their strength.

Unfortunately the structure was equally formidable as a manufacturing challenge. Chandra explains: “The dream was that it would be robotically folded. This is how, in theory, the process was supposed to work: each of these panels were supposed to be cut by a machine, then put on a table and folded by robots. In reality, folding each panel with a robot took at least half an hour. Folding it by hand took 30 seconds.

“So this thing kind of fell apart, and we were extremely disappointed because we were hoping to get a glimpse of our future. And so, out of a combination of ignorance and arrogance, we thought: ‘We can do a better job of this.’”

Failing electronics and gearbox duopolies

They settled on a goal: a tabletop robotic arm affordable on a scale that it wouldn’t have to replace 10 employees, or even one, but would be able to handle the simple repetitive tasks that still take up many hours of work for anyone in the business of making things. (Current test projects with clients include light manufacturing work, but also quality assurance – stuff like pressing a doorbell 10,000 times, each with a slightly different level of accuracy and pressure – and rapid prototyping.)

That was almost five years ago. The pair have hit their share of roadblocks along the way. Some, with hindsight, seem inevitable. Their goal was to go full time on Automata in March 2015, launch a Kickstarter campaign in July and ship robots by December that year.

“We had a fairly good looking, well-functioning prototype. And we were like: ‘Oh this is good, because this we can ship.’ And then we hit a wall because these things started failing,” said Chandra. “These Korean electronic mechanical components started failing left, right and centre. We would leave the robots fine, shut down, unplugged on Friday and we’d return on Monday and half the electronics were dead.”

But not every issue was foreseeable. Take gearboxes. “There are basically two companies that supply gearboxes to every robot company in the world,” Chandra says. “So if you’re a robot company today operating commercially, you’re buying gearboxes from one of these two pairs. And if you just buy gearboxes from these guys, it means you cannot make a robot for less than $9,000.”

So they had to build their own gearboxes, which led to a second set of problems and a realisation of why there aren’t many companies in the sector already. The measure of success for a gearbox is part precision, part lifespan. The ones currently on the market have a lifespan of up to 40,000 hours – four and a half years of continuous operation – and while the Eva arm isn’t intended to work for that long, it’s still a painful process to have to wait two months while a new revision undergoes testing.

Hardware struggles where software startups thrive

The eventual goal is a machine that can survive two years of operating eight hours a day. Once that’s achieved, Automata can widen its horizons: the team is already exploring novel ways of programming the arm itself, in an effort to further open up the potential of robotics to new areas, and is hoping to start incorporating some of the latest research on applying machine learning techniques to manufacturing.

Before then, simply getting the Eva out the door will be a big enough challenge, one that might have progressed a bit quicker if the technology community were more comfortable taking risks on hardware startups.

Compared to an app developer, where a team of 10 and a few million in funding can rapidly produce a service that is valued in billions (think WhatsApp), hardware takes more cash and time to develop.

“Currently the world’s most powerful company is a hardware company – Apple. Whether it’s going downhill or not is another story, but the fact is it’s been on top for the last five years and despite that, people don’t see the value for hardware companies. It’s a sad thing,” says Chandra.

When the Guardian first mentioned Automata, in a round-up of startups, the 133-word mention was enough to cause havoc in the office, Chandra tells me semi-reproachfully, with requests for information from potential customers preventing him from doing much else for a few weeks. “Now we’re at a point where we are hesitant to put out a press release because we’re tired of saying our robot is still not ready. Just a few more months.”

Chandra hopes that Eva’s eventual launch will hit hard, comparing the potential of robots with the smartphone or PC. “You had people and they were all hindered by this thing, and then suddenly they could do so much more. I would say that robots would do something similar, but towards labour-intensive tasks.”

Like many in his position, he’s less afraid of the downsides to automation than some commentators. “There are enough studies on both sides saying ‘Hey, if there are robots there’s actually more productivity and more labour’. Not necessarily more labour but, in general if a country is manufacturing more of stuff, the GDP’s gonna go up and in general, it’s gonna be a wealthier country.

“Whether that wealth’s concentrated with the few or distributed properly among everyone is more of a question for capitalism I guess but inherently, a robot is just another thing that will lead to doing more in less time with fewer resources.”